Potato Late Blight: History, Impacts, and Prevention

What is Late Blight?

Potato late blight is a serious plant disease caused by the pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Often mistaken for a fungus, this oomycete is actually related to brown algae and can rapidly destroy potato and tomato crops in cool, wet conditions.

This page provides essential information for farmers, gardeners, and the public to understand the disease, recognize its signs, and learn how to prevent its spread.

Protecting potato production is vital for food security and the local economy, especially in areas like Colorado's San Luis Valley.

For more detailed guidance, consult your local CSU Extension office.

Colorado's Late Blight Quarantine

Protecting Colorado Crops

In Colorado's San Luis Valley, a major potato-growing region, the state enforces a quarantine to prevent late blight. This area produces high-quality seed potatoes worth over $100 million annually and remains free of the disease.

Quarantine Rules:

- All seed potatoes entering quarantined counties (Rio Grande, Saguache, Alamosa, Conejos, Costilla, Mineral) must be certified and tested.

- Imports require inspections, health certificates, and lab tests on at least 400 tubers.

- Transport vehicles must be covered during summer months to prevent spore spread.

- Cull potatoes must be destroyed within 72 hours by methods like deep burial or composting.

- Report all potato plantings and any suspected blight to authorities.

Strict compliance is essential. One infected shipment could introduce the disease, leading to widespread losses and costly treatments. Violators face fines or penalties.

By following these rules, growers protect the industry and ensure safe, healthy potatoes for everyone. This aligns with historical lessons on quarantines to prevent pathogen introductions.

For more on regulations in Colorado, visit CDA's Plant Imports page or contact our program for the latest guidelines.

What Late Blight Looks Like

Signs and symptoms

Late blight affects potato plants and tubers. It spreads fastest in cool (50-70°F), moist weather with high humidity or rain.

On leaves and stems:

On leaves and stems:

- Small, dark green or brown spots appear, often on lower leaves.

- Spots expand into large, dark, water-soaked lesions that turn blackish/brown and necrotic.

- In humid conditions, white, fuzzy growth (spores) forms on the underside of leaves.

- Affected areas turn black and die, sometimes emitting a distinct odor in severe cases.

On tubers (potatoes):

On tubers (potatoes):

- Brown or purple patches appear on the skin, which may feel firm or leathery.

- Inside, the flesh shows reddish-brown rot that can extend inward.

- Secondary bacteria can cause soft, smelly decay.

The disease can kill entire plants in days, significantly reducing yields or causing total crop loss. It also affects related plants like tomatoes, showing similar symptoms on leaves, stems, and fruit. If you suspect late blight, contact your local extension service for confirmation; early detection is crucial for limiting spread.

Diagnosing late blight

Look for characteristic symptoms, especially the white spore growth. Lab tests, such as microscopy or DNA analysis (e.g., PCR), can confirm the pathogen.

Testing helps choose effective controls, especially as some strains resist common treatments (e.g., clonal lineages like US-23).

Control and Prevention

Since there is no cure for late blight, prevention is essential.

Follow these steps:

- Use certified, disease-free seed potatoes.

- Sanitation: Remove and destroy volunteer plants, cull piles, and weeds like nightshade.

- Cultural Practices: Plant in well-drained fields, avoid overhead watering at night, practice crop rotation (2-3 years with non-hosts), and use balanced fertilization.

- Resistant Varieties: Choose resistant varieties, including some transgenic options with genes from wild Solanum species, though resistance can evolve.

- Fungicide Application: Apply protective fungicides (contact and systemic, like copper-based) before symptoms appear, following label instructions. Rotate fungicides to prevent resistance and use weather forecasts or blight prediction tools (e.g., USABlight, Hyre, Wallin, or BLITECAST).

- Field Management: Scout fields regularly, destroy infected plants immediately, and hill soil around stems to block spores.

- Post-harvest: After harvest, store potatoes in cool, dry conditions and monitor for rot. Destroy foliage before harvest.

Integrated pest management (IPM) combines these methods for sustainable control.

For home gardeners, it’s important to rotate crops, space plants for air flow, and avoid planting potatoes near tomatoes.

Ongoing studies stress that parasites like this cannot be eliminated, requiring coexistence and global cooperation for food security.

Spread

Late blight spreads through:

- Infected seed potatoes or leftover tubers: The pathogen survives as mycelium in the soil.

- Wind-blown spores: Sporangia are carried by air currents from nearby infected plants.

- Rain or irrigation water: Water splashes spores onto healthy plants; zoospores swim in water to infect in cool conditions.

- Tools, equipment, or people: Movement between fields can spread the disease.

The pathogen's life cycle is rapid: Spores germinate in 3-5 days and producing new sporangia under favorable conditions (optimum 18-22°C or 64-72°F with moisture). Sexual reproduction can occur if mating types A1 and A2 meet, forming durable oospores.

Impacts

Late blight leads to:

- Crop losses: Reduced yields raise food prices and affect farmers' incomes, with potential for total destruction in uniform crops.

- Increased fungicide use: Adds costs and environmental concerns.

- Historical and modern threats: While historically leading to famine, it continues to threaten commercial potato production worldwide. U.S. outbreaks, such as those in 2009 from infected transplants, have caused significant losses.

In the U.S., annual losses from late blight can reach hundreds of millions of dollars.

Historical Background

The Irish Potato Famine

Potato late blight has a devastating history. The pathogen, first described by Dr. C. Montagne in the 1840s, played a major role in the Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852), also known as the Great Hunger. During this period, Ireland's population, heavily reliant on potatoes, decreased by at least 1 million due to disease and starvation, with an additional 1.5 million emigrating, many to the United States and Canada.

Key historical facts

- 1845: The blight wiped out much of Ireland's potato harvest, affecting millions and leading to widespread food shortages.

- Impact: The famine resulted in approximately 1.5 million deaths and spurred a significant wave of emigration.

- Lessons Learned: This event highlighted the risks of relying on a single crop, emphasizing the need for diverse agricultural practices and leading to advances in plant science.

Identifying the pathogen

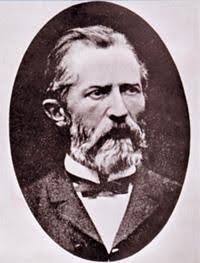

German scientist Heinrich Anton de Bary (pictured) proved in the 1870s that Phytophthora infestans causes late blight disease, laying the foundation for modern plant pathology.

German scientist Heinrich Anton de Bary (pictured) proved in the 1870s that Phytophthora infestans causes late blight disease, laying the foundation for modern plant pathology.

The pathogen likely originated in the Andes, with Mexico as a center of diversity. Its uncontrolled introduction to new areas led to devastating outbreaks, like the Irish potato famine.

This tragedy led to the establishment of plant pathology as a discipline and the implementation of U.S. plant quarantine laws in 1912.

Resources

- History and science of late blight (American Phytopathological Society)

- USABlight.org: Disease forecasting and alerts

Contact Us

Cheryl Smith

Seed Potato/Late Blight Quarantine Program Manager

Phone: 303-869-9073